Outbreaks, Alerts and Hot Topics: Measles and (Immune) Memory Loss

Column Author: Chris Day, MD | Pediatric Infectious Diseases; Director, Transplant Infectious Disease Services; Medical Director, Travel Medicine; Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine; Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Kansas School of Medicine

Column Editor: Angela Myers, MD, MPH | Pediatric Infectious Diseases; Division Director, Infectious Diseases; Medical Director, Center for Wellbeing; Professor of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine; Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Kansas School of Medicine

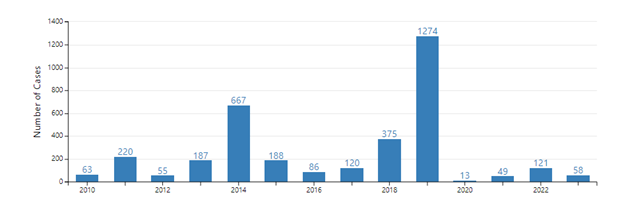

While we have had at least one local case of measles and 20 United States cases reported so far this year, this year’s numbers pale in comparison to 2019 (measles by year) or even to 2022 (Measles in The Link January 2023). So, by comparison, we have not a large outbreak so far. The “new” information on measles that I want to discuss came out in Science and in Science Immunology in 2019, so perhaps it’s not exactly a hot topic. So, let’s call this an alert, or a warning. I am alerting you that measles is a bad infection, that we now know at least some of why it is bad, and that we should be trying to vaccinate everyone we can against measles infection. And I hope we can find ways to share this understanding of measles with our vaccine-hesitant families in a way that motivates them.

We know measles vaccine can save lives, far more lives than might be expected based on death rates due to acute measles infection alone. Acute measles infections can be fatal (between one and three in 1,000 cases in the U.S.)1 and secondary infections associated with the acute measles infection (especially in low-income countries) can be deadly as well. But excess mortality after measles infections persists long after this immediate period. Studies published in the 1980s and 1990s show that the introduction of measles vaccines in low-income countries appeared to lead to large (30% to 50%) reductions in child mortality from all causes. Even greater benefits (up to 90% reductions) were found among the most impoverished children.2

So other than measles infection, what else does measles vaccination prevent? Measles infection can have a profound effect on immune memory, including both the ability to recall prior infections and also to recognize and remember new infections. For prior infections, these effects can be permanent in some way: the immune system after measles may react to these infections as though encountering them for the first time.

How does this response work? Measles enters the body through the respiratory tract where it infects macrophages and is transported to lymph nodes. In the lymph nodes, it enters memory T cells and B cells, infecting 20% to 70% of them. The immune system appropriately reacts to destroy these infected cells, but the process of clearing measles causes many of the learned responses to prior pathogens to be lost, even as robust immunity to measles develops. Consequently, the diversity of pathogen-specific antibodies is reduced, by between 11% and 73% of the total repertoire, following measles infection.3 Measles infection reduces the diversity not only of memory B cells, but also of naïve B cells, likely leading to a limited ability to respond to newly encountered pathogens.4 After measles, protection against another measles infection is iron-clad, but specific protection against other infections, regardless of whether they’ve been encountered before, will often be poor. It appears to take two to three years for protective memory immune responses to be restored.

While it may seem unlikely that measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine in the United States is as effective at preventing child mortality as it is in lower-income countries, data show large decreases in infectious disease-related mortality accompanying the decline in measles following the introduction of measles vaccine in the United States, England and Wales, and Denmark. It has been estimated from this data that, prior to widespread use of measles vaccine, as many as half of all childhood deaths from infectious diseases were related to measles and its immune sequelae.2

Measles is no longer endemic in the United States, but large local outbreaks can and have occurred when imported cases meet unvaccinated populations. An outbreak of this kind occurred in Orthodox Jewish communities in 2019, which had 75% of the 1,249 measles cases reported in the first nine months of that year.5 In another example, with an outbreak in Ohio in 2022-23, of 85 cases, only three had documentation of even one prior MMR vaccine. At least in part due to the rather remarkable ability of measles to spread, it is estimated that, to achieve herd immunity, 95% of the population needs to be vaccinated. High rates of MMR vaccination remain crucial for the health of those who can’t or won’t be vaccinated.6

Number of measles cases reported by year (Source: CDC.gov)

References:

- Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Measles. In Red Book: 2021-2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 32nd ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021.

- Mina MJ, Metcalf CJ, de Swart RL, Osterhaus AD, Grenfell BT. Long-term measles-induced immunomodulation increases overall childhood infectious disease mortality. Science. 2015;348:694-699. PMID: 25954009. PMCID: PMC4823017. doi:10.1126/science.aaa3662

- Mina MJ, Kula T, Leng Y, et al. Measles virus infection diminishes preexisting antibodies that offer protection from other pathogens. Science. 2019;366(6465):599-606. doi:10.1126/science.aay6485

- Petrova VN, Sawatsky B, Han AX, et al. Incomplete genetic reconstitution of B cell pools contributes to prolonged immunosuppression after measles. Sci Immunol. 4(41):6125. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125

- Patel M, Lee AD, Clemmons NS, et al. National update on measles cases and outbreaks — United States, January 1–October 1, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:893-896. doi:15585/mmwr.mm6840e2

- Tiller EC, Masters NB, Raines KL, et al. Notes from the field: measles outbreak — Central Ohio, 2022–2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:847-849. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7231a3

See all the articles in this month's Link Newsletter

Stay up-to-date on the latest developments and innovations in pediatric care – read the February issue of The Link.